|

| Vergil flanked by two Muses |

The Aeneid

is a cornerstone of Western Literature, the pinnacle of Latin poetry, and one of the three greatest epics produced in the ancient Mediterranean world (the other two being Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey). In other words, The Aeneid is a classic, a masterpiece.First, we must examine The Aeneid's models:

The Supremacy of Homer – The Iliad

|

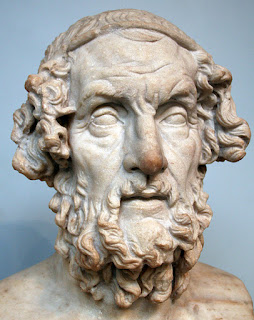

| Homer, Roman copy of original Greek, now lost. 2nd Century B.C. |

As long as humans have walked these lands, they have told stories, tales of heroes and gods, of weapons and peace, of love and loss. When these stories were first being woven, there was no alphabet, no writing -- so our ancient ancestors told them orally, passing on the tales from person to person, parent to child, rhapsode to king &c.

One such story from ancient Greece told of a long war which was fought between the kingdoms of Greece and the kingdom of Troy. The war (we are told by mythographers) was due to a Trojan prince kidnapping Helen, the Queen of Sparta, and taking her to Troy. The Greeks besieged Troy and, after a ten year struggle under its mighty walls, finally gained the walls through trickery, and then set the grand city aflame.

There really was a city of Troy: excavations of the ruins began a little over a hundred years ago in modern-day Turkey. The city seems to have been destroyed by weapons and fire in the late 13th or early 12th century B.C., a plausible date for the war described in these stories. From this time (late 13th or early 12th century B.C.) onwards, the Greeks told stories about this epic struggle. Finally, around the late 8th B.C., a man whom history calls Ὅμηρος (Grk: Homeros; Eng: Homer) wrote down the story which he had heard and had been telling using the newly devised alphabet. This story has come down to us in its present form as The Iliad.

|

| Akhilles and Patroklos |

The rage of the greatest Greek warrior, Ἀχιλλεύς (Grk: Akhilleus; Eng. Achilles) drives the actions, for the poem begins:

The rage of Akhilles begins when he is wronged by his superior officer and his anger intensifies as he seeks to avenge the murder of his closest friend by slaying Hektor, the noblest and eldest prince of Troy. The wrathful hero, unstoppable and terrible, slays his enemy, and he wrongs the latter's body in his anger.

|

| The Triumph of Achilles |

It is there that The Iliad ends.

The Supremacy of Homer – The Odyssey

There were other epic poems (scholars have identified seven or eight or them), lengthy tales which explained how the Trojan War began, tales which told of other struggles and deeds during the war apart from the rage of Akhilles (The Iliad) and tales which told of the homecoming of the victorious Greeks. These epic poems in their original forms are mostly lost to us (fragments exist), but the stories are so well known that we know the basic plots. Let's put it this way: it would be similar to future generations of readers, hundreds of years from now, losing all seven books of the Harry Potter series except for books two and six. One would have to reconstruct the overarching plot which develops over the course of all seven books based on what someone else (another author or reader) who had read or said something about the lost books hundreds of years ago before they were lost. Sounds like fun, huh?One of these homecoming stories has come down to us in the epic poem format: this poem is known as The Odyssey, the story of the wanderings of the Greek hero Ὀδυσσεύς (Grk. and Eng: Odysseus; Lat: Ulysses) and his return to his home after fighting in the Trojan War. Odysseus’ wanderings, how the man deals with the situations and people/creatures he encounters drives the action, for the poem begins:

Ancient tradition also ascribes the composition of The Odyssey to the same Homer whom it claims wrote The Iliad – we have no good reason to assert otherwise.

So, in recap, The Iliad is about the rage of Akhilles, the war at Troy, while The Odyssey is about a man, Odysseus. Homer, a Grecian singer, penned both epics which come from a long legacy of being sung for people.

For the past 2,700 (or so) years, The Iliad and The Odyssey have remained two of the best and most popular works of literature ever written.

The Legend of Æneas

One of Troy’s many princes was Αἰνείας (Grk: Aineias; Latin: Æneas), who fought at Troy. In Homer’s Iliad, the prince barely manages to escape the man-slaying wrath of the Grecian Akhilles. The god Poseidon sees the two fighting and notes that Aeneas cannot stand before the superior Akhilles:

“Oh alas, surely there is distress for great-hearted Aineias,This is strange, in that Poseidon favors the Greeks – why would he come to the aid of a Trojan prince? It is clear that the need for Aeneas to survive the Trojan War is something decreed by fate (“His fate is to escape…”), which is why an anti-Trojan god would stoop down to save a Trojan’s life. At the time when Homer wrote down the story of The Iliad, there existed a myth that Aeneas would escape the destruction of Troy and found another kingdom afterwards. Homer NEVER says that Aeneas will go to Italy, nor does he claim that the Trojan prince will found Rome - indeed, most Greek mythographers just record that Aeneas escaped due to his piety. His post-Troy flight to Italy was a part of the story which was taken by the Romans some time later.

Who quickly shall go down to Haides, overpowered by Peleus’ son!

By obeying the words of far-shooter Apollo,

He is like a child; and no one shall ward off his baneful ruin!

But why does this blameless man suffer pains

In vain, because of the pains others made? Always agreeable

Gifts he gives to the gods who hold wide heaven;

But come now! Let us lead him away from death,

Lest Kronos’ son be angered, if Akhilleus

Should slay him. His fate is to escape

So that not unseeded be his race, blotted out, destroyed,

The race of Dardanos, whom Kronos’ son loves,

All those who were born of him and mortal women.

For indeed, the son of Kronos now detests the race of Priam,

But the might of Aineias shall rule the Trojans,

Their children’s children, whoever shall be born hereafter.”

-Homer, The Iliad, Book XX. trans. is my own

|

| Aineias Carrying Ankhises, Black figure oinokhoe 520-510 B.C. |

Indeed, this idea of Trojan refugees led by Aeneas fleeing to Italy and founding the Romans was very popular in Rome from at least the 5th Century B.C. onward. It was a well-known story in Vergil's day. Could Trojan refugees have fled to Italy and established a colony which would become Rome or in some way influence Rome’s founding? Absolutely: the Etruscans, a people who had a great deal of influence on early Rome, were said to have hailed from Phrygia and its environs - the land of ancient Troy. The theory isn't that far out-of-left-field.

|

| Aeneas Flees Burning Troy, Federico Barocci 1598 |

Romulus, Augustus, Vergil, and the Æneas Myth

|

| Vergil |

It was around this time that Rome’s first princeps ("leading citizen" - a carefully crafted title which made Augustus emperor in everything but name) asked the poet Publius Vergilius Maro, a native of a small town near Mantua in northern Italy, to write a poem about Rome’s greatness. What Vergil wrote was The Aeneid, an epic poem in the style of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey which told of Aeneas’ (Augustus’ great ancestor) flight from Troy, his odyssey through the Mediterranean, and his landing in Italy. The legend of Aeneas was already there in the Roman mind– it just needed Vergil to compose it into an epic poem.

Vergil began writing the poem in 29 B.C. and spent the next ten years writing and editing it. He took a sea voyage to Greece in 19 B.C. and fell ill. Upon returning to Italy, he died at Brundisium harbor. A perfectionist to the end, his final wish was that The Aeneid be burned, for he had not perfected it – it was complete as a story, but there were unfinished or unpolished lines of poetry which he had intended to complete before his death. The emperor Augustus forbade the poem from being burned and ordered it to be emended and published instead.

The Latin Epic – The Æneid & Its Greek Predecessors

Though The Aeneid is written in Latin and concerns the founding of Rome, it is almost entirely built on its Greek predecessors, mostly Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

Firstly, the title Vergil gave to the poem was Æneis, the Greek name for Aeneas, thus invoking the older epic poetry of Greece. The poem’s first line outlines the story:

Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris

Of weapons and a man I sing, who from the shores of Troy…Let us remind ourselves that Homer begins The Iliad by speaking of the rage of Akhilles and the war at Troy, while The Odyssey begins with mentioning the man who wandered through the Mediterranean. Vergil is alluding to both epics by saying that his poem is about weapons and war (Arma) and a man (virum). The Aeneid combines both The Iliad (war and weapons) and The Odyssey (a man who wanders), for Books I – VI of Vergil’s poem follow Aeneas (a man) and his wanderings about the Mediterranean, while Books VII – XII follow Aeneas’ war with the Italian tribes.

Books I – VI (The Odyssey books) of The Aeneid quite closely follow the plot of the Homeric poem: Odysseus, a Grecian hero from the Trojan War undergoes many hardships as he tries to return home.

Among these trials is an episode in which his men accidentally release violent winds from a bag, causing a storm which blows them off course (Aeneid Book I). After several more adventures, Odysseus washes up on the beach of the island of Skheria where he is discovered by a princess (Aeneid Book I). He is well received by the royal family of Skheria and is asked to tell his tale (Aeneid Book I), so Odysseus tells of his travels and adventures in the Mediterranean (Aeneid Books II & III).

One of his adventures was dealing with a man-eating Cyclops (Aeneid Book III), and another was a chilling foray into the Underworld to speak with the dead (Aeneid Book VI). Book IV, the passion of Queen Dido for Aeneas, has no comparison in Homer’s epics; instead, the book is charged with references to Greco-Roman love poetry and it reads almost exactly like a Greek tragedy seen through Roman (Vergil) eyes.

Meter

Dactylic hexameter runs in the following template:The first five feet (indicated by Roman numerals) are dactyls (long short-short/quarter note, eighth-eighth note/daa da-da) and the sixth foot is a spondee (long-long/quarter note-quarter note/daa-daa). Each of the two short syllables in first four feet, the eighth notes, can be replaced by a single long, a quarter note (da-da becomes daa).

Keep also in mind that the fifth foot is almost always is a dactyl, though spondaic lines (where the fifth foot is a spondee) do pop up every now and again and cause delight for the teacher and consternation for the poor student struggling to make sense of his or her scansion - Vergilian spondaic lines are rather on the rarer side. Regardless, I've roped off the fifth and sixth feet in purple in the above template as "out-of-bounds" for typical metrical tinkering.

The caesura ("cutting") indicates a pause in the line and are marked above by either the blue or green railroad tracks. These are traditionally called the strong/masculine and weak/feminine caesura, respectively (I avoided the color pink for the feminine caesura in order to throw something in the face of traditional sexism in Classicism - green is a much better color than pink); alternately, they are also respectively known as the penthemimeral ("occurring at the fifth-half measure") caesura and the trochaic ("occurring after the trochee") caesura - these are infinitely cooler names than the aforesaid. The first line scans as:

The books of The Aeneid can be summarized as follows:

- Book I: Invocation of the Muse. Aeneas encounters a storm sent by Juno and is cast ashore at Carthage, where he is welcomed by Queen Dido.

- Book II: (flashback) The hero tells Dido of the Trojan Horse, the destruction of the city, and his escape from Troy with his father, Anchises, and his son, Ascanius Iulus.

- Book III: (flashback) The wanderings of Aeneas: Thrace, Delos, Crete, harpies, meeting with Helenus and Andromache at Buthrotum, the death of Anchises, Cyclopes.

- Book IV: Dido's mad passion for Aeneas. Jupiter commands Aeneas to depart Carthage for Italy. Dido kills herself.

- Book V: Aeneas reaches the west coast of Sicily. Funeral games for Anchises.

- Book VI: Aeneas with the Sibyl at Cumae. He meets Anchises in the Underworld. Sees the future greatness of Rome.

- Book VII: Re-invocation of the Muse. Aeneas lands in Latium. King Latinus promises Lavinia to him. Juno and Allecto stir up the Italian tribes against the Trojans. Catalogue of Italian warriors.

- Book VIII: Aeneas seeks the help of Evander and the Etruscans. Story of Hercules and Cacus. Receives divine armor from Vulcan, including the shield depicting Rome’s greatness.

- Book IX: Turnus attacks the Trojan camp. The deaths of Nisus and Euryalus. The camp comes under heavy attack.

- Book X: The gods convene. The Tuscan fleet arrives. Turnus kills Pallas and Juno in turn rescues Turnus from Aeneas. Aeneas kills the wicked Mezentius.

- Book XI: The funeral of Pallas. Drances wants to leave Turnus’ alliance. Diomedes refuses to join the Italians against the Trojans. The Trojans attack. Camilla is killed in battle.

- Book XII: Single combat between Aeneas and Turnus, but trickery causes the fighting to begin anew. Trojans attack the city. Amata commits suicide. Aeneas finally kills Turnus in single combat upon seeing Pallas’ belt upon him as a spoil of war.

No comments:

Post a Comment