The 1st Catilinarian of Marcus Tullius Cicero, given in the Roman Senate at the Temple of Jupiter Stator on the 8th of November, 63 B.C. (published in 60 B.C.)

Background

In 63 B.C, Catiline, running for Consul for 62 B.C, threw in his lot as a candidate for the poorer classes in Rome, and advocated a tabulae novae, a cancellation of all debts, as well as land redistribution; these topics were always popular and many a sensible politician played to the wants of many for their votes. Bribery, as usual, was a large part of the campaigning process, and Cicero, acting in his capacity as Consul, sought to put an end to all of these intrigues by passing legislation (Lex Tullia de ambitu) to make banishment for a ten year period the punishment for bribery; a harsh penalty that, enough so that it made even the most shrewd calculator think twice.Catiline, rightly so, believed this move to be personally aimed specifically at him, and, as a result of it, could possibly lose him the Consulship. He plotted to murder Cicero on the Field of Mars as the latter was overseeing the election process (the duty of each Consul). Cicero heard of the intention and postponed the elections. Convening the Senate, he questioned Catiline before all in the chamber, whereupon Catiline offered as his answer:

"'What dreadful thing, pray,' said he, 'am I doing, if, when there are two bodies, one lean and wasted, but with a head, and the other headless, but strong and large, I myself become a head for this?' Since this riddle of Catiline's referred to the senate and the people, Cicero was all the more alarmed [...]."

-Plutarch, Life of Cicero XIV.6-7

When the elections were held, Cicero set his friends and clients all about him as bodyguards, while he himself wore a breastplate under his toga. Great care was taken that all could see this bulky armor underneath his clothing and that the image would be burned into their memories in case he ever needed to bring it up again (and indeed he did in the following speech). Memory is a powerful tool for a skilled orator.

And so, the Romans elected Silanus and Murena as their Consuls for 62 B.C.

Catiline, having failed twice in his dream to obtain the Consulship (for years 63 and 62 B.C.), considered the only redress of this wrong to be the overthrow of the government in his favor. Gathering about him Sulla's veterans, debtors, and disillusioned, bored youths looking for some excitement and a place in the new regime, Catiline sent Gaius Manlius (a centurion of Sulla's and a well-known spendthrift in huge debt) northwest to Faesulae in Etruria to raise an army there and to cause general unrest.

Catiline made plans at Rome that parts of the city would be set on fire and a large portion of the Senators murdered. During the chaos, the conspirators would escape from the city, join up with Manlius' army marching southeast, and retake the city with their newly bolstered numbers. Special care was given to the murder of Cicero, whom Catiline blamed for his recent setbacks. The military standard to assemble at the camp was raised on October 27th and the rebellious forces waited further orders to march on the city.

Having become rather nervous by these seditious plans and meetings, a certain Quintus Curio got cold feet and divulged to his mistress Fulvia the entire plot. Fulvia, an upperclass woman of questionable reputation, managed to relay this information to Cicero, who set his own spies into motion and made this Curio one of his prime informants. In the Senate on October 21st, Cicero was able to produce letters written in an anonymous hand which spoke of a conspiracy in the city and he told the Senators that Manlius would be prepared to attack on the 27th. A Senatorial Decree was passed the next day on the 22nd, "so the the Consuls may see to it that the Republic should suffer no harm" ("Videant consules nequid res publica detrimenti capiat"). When further news reached Rome of military camps being pitched in Etruria outside the will and authority of the Senate and the People, Cicero, armed with Dictatorial powers invested in him by the Decree, stationed garrisons at strategic points and continued to gather information of the plot.

Catiline, in order to throw suspicion off, offered himself into the custody of chief men of the state to prove his innocence: first to Marcus Lepidus, who refused him; next, he offered himself to Cicero. Cicero recounts this in the following speech when he blithely remarks that when Catiline dared to come to him...

"Cum a me quoque id responsum tulisses, me nullo modo posse isdem parietibus tuto esse tecum, qui magno in periculo essem, quod isdem moenibus contineremur [...]"

-Cicero, In Catilinam Oratio Prima

"When by me also that response thou hadst borne, that I in no way am able within the same walls of my home be safe with thee, when in great danger I already am, given that within the same city walls we are penned in [...]"

Having received that eloquent "no", Catiline made his way to Quintus Metellus, a Praetor, and one of his associates, who finally received him. Able to obtain no further succor from his fellow conspirators, Catiline, perhaps sensing the walls closing in, ordered the chief instigators of the plot to meet at the house of Marcus Laeca on the night of November 6th. Gathering in secret there without Metellus' knowledge, Catiline upbraided his fellows to such a degree that two men volunteered to prove their worth by departing immediately for Cicero's home and murdering the Consul at daybreak at his morning salutatio, the daily greeting of clients and friends.

Cicero, whose spies were very good, learned of this immediately and set armed guards at his locked and barred door; the cowardly would-be murderers turned away from their bloody task.

Argument

Here's where

things become tricky: the following speech, as we have it, was

published in 60 B.C., three years after the fact; it is unknown what parts of the

speech were said on the morning of November 8th, and which were added

later by Cicero's editorial hand.

I like to believe that the events of that morning went as follows:

Enough was enough: though without any hard evidence of Catiline's guilt, another attempt had been made upon his life, so Cicero made his move. Acting as Consul, he convened the Senate on the morning of November 8th at the Temple of Jupiter Stator, "Father Jove the Stayer", an ancient and well fortified place near the Forum; this was a place sought for in times of emergency and danger, so to all the Senators it was clear the severity of the danger in which the Consul felt they were. A coterie of armed Knights stood about the temple (ancient Rome lacked what we would consider a police force).

Acting the capacity of a magistrate being given Dictatorial powers (conferred on him by the Senatorial Decree passed on October 22nd), Cicero probably planned to give an update on the conspiracy by informing the Senate of the would-be assassination attempt upon himself. He was certainly willing to lay the blame at Catiline.

If Cicero had prepared any words with the expectation that Catiline would leave the city after the assassination attempt had been made, then imagine the orator's surprise when Catiline showed up, ostensibly to continue to throw suspicion off of himself.

So what to do about him?

Execution?

Though Cicero claimed that he could have ordered Catiline's execution, the actual legality of such an assertion are a little hazy: it was unlawful to order a citizen to be executed without honoring said citizen's right to appeal the decision of the sentencing before a Tribune or before the People - this was called provocatio ad populum. And even though Cicero mentioned several times in the speech that he has been given the legal authority to execute Catiline by the Senatorial Decree and that there are several precedents for execution (most notably in the case of Tiberius Gracchus), the legality of those precedents stood on shaky ground. In theory, a Dictator (or quasi-Dictator, in this case) could ignore a provocatio, but the law technically still stood.

Cicero clearly didn't want to impose the death penalty on Catiline outright, for one of two things would have happened:

- Catiline would have just left the temple and gone into banishment - see below. The accused man would have just left from the city and then joined his abandoned army without his guilt declared. Cicero would have to work over the Senators and the People more to convince them of the man's guilt.

- Catiline would have called a provocatio ad populum, and Cicero would have had no choice but to honor it.

Catiline had already been acquitted so many times before, and certainly he would have escaped these baseless accusations just as easily; therefore, the Senators had to first be convinced of his guilt.

However, if Catiline were as guilty and dangerous as Cicero made him out to be, then how did the orator not blame himself for acting to save his city from a deadly enemy by resorting to executing the criminal - he's had these extraordinary powers for twenty days now!

Easy: take the blame himself.

Blaming himself of "inertiae nequitiaeque" -"inaction and negligence", Cicero moved on to convince the Senators of Catiline's evil nature and criminal activity, especially that he was the illegal general of anti-government military camps just a short march away from the Capital. Past crimes were alluded to, such as the murder of his wife and son, his seduction of the Vestal Virgin, several nondescript murders, the plot to kill Cicero on the Field of Mars; but these were mere allusions, so tenuous and flimsy these vague accusations would be hardly be

admissible in any court ("There was once this rumor that at one time

perhaps the defendant did something bad...") - they were merely small attacks part of a larger character assassination piece.

Banishment?

Cicero then muses on the idea of banishment for Catiline. In exsilium, "into banishment", was a curious feature of Roman law: it allowed an accused or even

guilty citizen to just leave the city in order to escape punishment (Cicero himself described banishment as not a punishment, but an escape from punishment.)

The continued absence of the banished provoked the Senate to declare his property and estate confiscated, and his fellow-citizens were required to deny him water and

fire (interdictio aquae et ignis - "fire and water" being the traditional gifts of hospitality) and harm or murder him if able. The banished's civitas, his "citizenship", remained intact as long as he did not give it up himself by attaching himself to a foreign power (there existed no law which could strip a Roman citizen of his citizenship [cf. Ciceronis Pro Caec. 34] - he had to do it himself). The banished could be recalled with his property restored (this happened to Cicero himself).

So in this instance, not only was hard evidence of criminal activity lacking, but the idea of ordering Catiline into banishment would be not only illegal, but highly unpopular. "How could the Consul order the exile of a Roman citizen, a patrician no less, merely based upon hearsay and, at best, circumstantial evidence?" the People would say. It would not do. Catiline would have to leave voluntarily - but he had to leave with his guilt plain and clear, with the word hostis on every Senator's lips - "enemy of the state".

So Cicero merely "advises" upon the idea of banishment.

Escape?

In the end, the orator instead resorted to telling Catiline to leave the city and underscored that he left of his own free will, not as an exile. Having dragged into the Senatorial gathering the nasty and disgusting rumors of the foul things in his private life of which he had been accused, Cicero then mocked the man openly, all the while portraying himself as the apologetic magistrate who was merely trying to survive and keep his well-loved Republic in one piece - and, in the end, no one came to Catiline's defense, as Cicero pointedly told him.

The goal in doing this was to bait Catiline into becoming so angry that the conspirator lost his cool and stormed out of the chamber.

In so doing, not only had Cicero removed a violent seditionist from the city, but the man's guilt was palpably felt by all. How vague and ill-defined would those references to Catiline's past crimes and current accusations of treason seem if the accused all of a sudden excused himself angrily from the city, a thing which the Consul said that he had already planned to do in order to carry out his agenda of murder, fire, and mayhem? If he's guilty of this one thing, surely he is guilty of everything else said of him, yes?

It is a testament to Cicero's persuasive powers that he, a novus homo of extra-Roman birth, was able to turn the Roman Senate against a member of one of their most ancient Roman families.

The speech can be outlined as follows:

November 8th, 63 B.C.

So, when Catiline arrived at the Temple of Jupiter Stator, the armed Knights let pass by this man for whom they had been stationed there in arms. According to Cicero, no one greeted or spoke to Catiline. Once Catiline took his seat on the bench, the Senators nearby moved away from him, emptying their places next to him. A hush fell over the room. Heaven knows what Catiline expected to happen.

"Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?"

Up to what point will thou abuse, Catiline, our patience?

I like to believe that Catiline's first thought was something equivalent to "Ah, shit."

|

| Cicero: "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1XZGHOxnCto" |

Up to what point, Catiline, will thou abuse our patience? For how long yet will that damnable rage of thine us make fools? To what end shall thine unbridled recklessness1 cast itself about?

Oh, thou! Has not2 the nighttime guard set on the Palatine3, has not the city’s watches, has not the fear of the People, has not this assembly of all good men, has not this most well-fortified place for holding the Senate4, have not these men's faces and countenances, moved thee -- have they not?

Wide open lie thy plans! - dost thou not realize that?

Thy conspiracy is strangled by the knowledge held by all of these men! - dost thou not see that?

What of last night? What on the prior night thou didst do?5 Where were thou? Whom thou didst summon? What sort of plan thou didst make? Whom of us here dost thou suppose is ignorant of all these things?

O tempora! O mores!6

The Senate understands these things.

The Consul7 sees them; this man, however, lives.

He lives?

Even more so, even also into the Senate he has come, in public decision-making he takes a part, he sets down and marks with his eyes to slaughter, every single man, each one of us. We, moreover, we brave men seem to have done enough for the Republic, if that bastard’s rage and weapons we should avoid. To death! For thee, Catiline, to be led to death by the order of the Consul should have long since now occurred, and upon thee ought to be thrust the plague which thou against us art plotting.

Did not a man most well-regarded, Publius Scipio8, the Pontifex Maximus9, do away with Tiberius Gracchus10, who was moderately undermining the state of the Republic, all while Publius was acting as a private citizen? But Catiline? Shall we him, who the globe of the Earth by slaughter and also by conflagrations to lay waste -- for this he lusts after -- shall we the Consuls endure him to the former?

For other precedents -- which are exceedingly ancient -- I pass over11, such as how Gaius Servilius Ahala12 felled Spurius Maelius13 , who for a revolution was zealous, and with his own hand he slew him.

There once was, yea there once was at some time in this Republic, yea, some courage, so that brave men might with harsh penalties check a deadly citizen than they would a most bitter enemy14. We have a Senatorial Decree15 against thee, Catiline, powerful and serious, for not lacking is the Republic’s wisdom, nor the authority of this rank; we, we, I say openly, we the Consuls are lacking in our duty.

It was decreed once in the Senate that Lucius Opimius16 the Consul should see to it lest the Republic suffer any harm17; not a night, not a single one passed; there was slain on account of certain hints of sedition, Gaius Gracchus18, who descended from a most famous father, and grandfather, all his ancestors19; there was slain along with his children, Marcus Fulvius, a man of Consular rank20.

By means of a similar Senatorial Decree, to Gaius Marius and Lucius Valerius21, Consuls both, was entrusted the Republic; surely there passed one day for Lucius Saturninus22, the People’s Tribune, and Gaius Servilius23, a Praetor24? Yes, their death and the Republic’s capital penalty was delayed, surely. No? Was it not?

But indeed, at this time, we for a twentieth day25, we endure to grow dull the sharp sword’s edge of these men’s authority. For we have this kind of Senatorial Decree, one which truly is enclosed only in writing tablets, as if it were a blade buried in a sheathe; according to this Decree, forthwith is it proper for thee thou to be slain, Catiline. Thou livest, and thou livest not to place aside thine insolence, but to strengthen it. I desire, Fathers and Enrolled, to be merciful; I desire in such dangers of the Republic not to seem unraveled, but now only myself can I myself of negligence and inactivity condemn.

Military camps!26 Yes, there are military camps in Italy, against the People of Rome, camps pitched in Etruria’s mountain passes27, and there grows day by day the enemy’s number! Moreover, these camps’ general and the leader of the enemy28 is within the city’s walls and even now in the Senate ye see him, who is plotting some internal daily destruction for the Republic.

If I will now bid thee, Catiline, to be arrested, if then I bid thee to be slain, I believe I will have to be afraid lest good men may not say that this slaying had been carried out by me too late, but rather that it was too cruelly done. But I this slaying, which long since should have been done, because of this certain reason not yet am inclined to carry out. At last thou shalt be slain, when there is no one so wicked, no one so lost, no one so like unto thee that shall ever be able to be found who would say that thy slaying had been done not lawfully. As long as there will be anyone who thee to defend may dare, thou shalt live, and thou shalt live thusly, as thou live'st now, by my many and resolute guards beset, lest thou may'st be able to stir thyself against the Republic. Many persons’ eyes are on thee, and their ears as well, though thou do not perceive them -- they shall on thee, as they have up until now done, watch and guard.

For even more so, what, Catiline, now further canst thou await? If neither the night by its shadows can hide thine unlawful meetings, nor can a private home within its walls contain the voices of thy conspiracy, if all the shadows are alighted upon, if all the walls fall down? Change now that mind of thine! Trust in me -- forget slaughter and conflagrations! Thou are beset on all sides; because of the light more clear to us are thy plots, these very plots now with me thou art allowed to review - if thou can'st:

Dost thou remember that I, on the Twelfth Day Before the Kalends of November29, said in the Senate that there would be, decked out in arms on a certain day -- the Sixth Day Before the Kalends of November30, in fact -- Gaius Manlius, a follower of thine insolence and a servant of thine? It did not get past me, did it, Catiline? Not only this deed, so great in and of itself, so shameful and unbelievable, but truly, this is something to be much more wondered at: that I knew the day of it?

I spoke, yes I, likewise in the Senate that the slaughter of the aristocracy thou set on the Fifth Day Before the Kalends of November31, when at that time many leading men of the State did flee from Rome not only to save themselves but so as to keep thy plots in check.

Thou art not able to deny that thou on that day by my guards, by my care thou were hemmed in and thou were not able to move against the Republic. What of the fact that when at the departure of the rest of the senators thou were saying that, nevertheless, thou wouldst be content with slaughter of us who remained?

What! When thou were fully confident that Praeneste32 on the very Kalends of November33 thou wouldst seize in a night raid, didst thou not realize that yon colony by my bidding, by my garrisons, guards, and watchmen had been fortified?

There is nothing thou do, there is nothing thou plan, there is nothing thou think which not only have I heard of, but likewise I do see and plainly perceive.

Review further with me that night before, for now shall thou understand how much more rigidly watchful have I been for the well-being of the Republic than thou hast been for its destruction:

I say that thou last night were come to the street of the Scythe-makers -- not covertly shall I say anything -- to Marcus Laeca’s home; having come to the same place were several allies of the same madness and wickedness.

Thou dost not dare deny it?

Why art thou silent?

I shall prove it, if thou deny it. For I see that here in the Senate are those certain men who were together with thee.

O gods immortal!

Where-ever are we?

In which city do we live?

What Republic do we have?

Here, here there are in our number, Fathers and Enrolled, in this whole world's most hallowed and serious council, there are those who dwell on the destruction of all of us, dwell on this city's -- nay! even up to the entire globe’s -- ruin! I the Consul can see these men! And concerning the Republic I am asking their opinions, even though they ought to be put to the sword -- but not yet have I even wounded them with my words!

Thou were, then, at Laeca’s that night, Catiline; alloted thou the parts of Italy; decided thou whither each man was pleased to depart; chose thou those whom at Rome thou wouldst leave behind, whom with thee thou wouldst lead forth; wrote thou down the city’s parts to be set aflame; made sure that thou thyself already by then would depart; spake thou did that there was for thee a little bit of --yes, even still now!--a delay: I suppose it was the fact that I still lived.

Found were two Roman Knights who would set thee free from that anxiety of thine and these very men on that very night a little while before dawn promised to slay me in my bed.

These things, all these things, did I learn when thy meeting was scarcely broken up. My home with greater guards I fortified and made strong. I shut them out, those whom thou had sent to greet me early in the morning, those whom I had already tipped off to many of the highest-ranked men that they would come to me at that time.

Since these things are so, Catiline, begone whither thou hast begun! Depart at last from the city! Open lie the gates! Set forth!

Exceedingly too long have those Manlian camps of thine longed for their general, for thee!

Lead out with thee also all those men of thine, at least as many as possible; cleanse the city.

From a great fear me thou shall free, if only between thee and me may there be a wall.

With us to dwell no longer art thou able; I will not bear it, I will not suffer it, I will not allow it.

Great must be the thanks given to the gods immortal and also to this very god, Jove Father the Stayer, a most ancient guardian of this city, given that this so foul, so horrible and so destructive a plague for the Republic we have so often since escaped.

It is not often in one person that the supreme well-being of the state is to be risked.

When every occasion thou, Catiline, hast plotted against me as the Consul-elect, not by public guards, but by private diligence have I defended myself. When at the last Consular elections thou wished to slay me as acting Consul and slay thine opponents in the Field of Mars, I stopped thy wicked attempts by a guard of my friends and mine own resources, with no public uproar roused; in sum, however many times me thou hast attacked, by mine own skill have I opposed thee, though I have long since seen that my destruction has been intertwined with a great calamity for the Republic.

Now openly the Republic entirely thou art attacking, the temples of the gods immortal, the homes of the city, the lives of all the citizens, the entirety of Italy to ruin and devastation thou dost call.

Wherefore, since thy slaying, a thing of primary importance both to this government and to the precepts of our ancestors is proper, I not yet dare to do: I shall do something which is in regards to severity more lenient and in regards to the common well-being more useful.

For if I will have bidden thee to be slain, there will yet stay inside the Republic the remaining handful of thy conspirators; but if thou, as I have already urged thee, will have left, then drained out of the city will be thy companions, the great and dangerous dregs of the Republic.

What is it, Catiline?

Thou dost not hesitate to do with me bidding thee that which already of thine own accord thou were doing?

The Consul bids the enemy of the state to depart from the city.

Sayest thou to me, "Am I to go into banishment?" I do not bid thee; but if thou consult me, I advise it.

For what is there, Catiline, which in this city is able to please thee? In this city, there no one exists outside of that damnable conspiracy of lost men, who thee does not fear, no one, who thee does not hate. What of thy well-known vileness at home? What has not been seared into thy life? Of private affairs, what indecency does not stick to thy reputation? What lust from thine eyes, what crime from thine hands ever, what vice from thine entire body has been lacking? In regards to the youth, is there any to whom, when by corruptions’ allurements thou hast ensnared, thou has not also handed out to them either a sword for lawlessness or a torch to light the way for their nightly lustful debaucheries? What now? Recently when thou hadst made empty thy home with the death of thy last wife for new wedding vows, didst thou not also add to this crime with another unbelievable crime? But this crime I myself pass over and easily do I endure to be quiet, lest in this State the enormity of such a crime may not either seem to have occurred or not seem to be punished. I pass over the ruination of thy fortunes, all which thou shall realize are hanging over thee for the next Ides; nay, I come to the following, which not only pertains to the private disgrace of thy vices, nor only for thy domestic hardship and shame, but for the sake of the Republic and also for the lives of all of us and our safety.

Can today's sunshine, Catiline, or the gentle breeze of this day to be joyful to thee, since thou know'st that among these men there is none who does not know that thou on the Day Before the Kalends of January when Lepidus and Tullus were Consuls, thou stood in the Comitium with a weapon, and thou made'st preparation for the slaying of a handful of Consuls and leading men of the State? That it was not some change of thy mind nor any fear thou had, but the sheer luck of the People of Rome that stopped thy crime and madness?

And now those crimes I leave out -- for neither are they hidden, nor are they not too many, as it were, committed afterwards -- so many times when I was Consul-elect, so many times when I was Consul thou didst attempt to slay me! How many times have I escaped thine attacks, fencing-like lunges hurled at me? So many times that they did not seem able to be avoided except by a certain parrying, and as they say, a feint of the body! There is nothing thou art accomplishing, and yet, not even art thou ceasing from trying and wishing to try to accomplish them. So many times from thee already has been twisted that blade from thy hand, so many times has it fallen because of some accident and slipped away! Yet to be absent from it, thou art no longer able. Indeed, in what holy ceremonies has that blade been consecrated and offered by thee I know not; though think'st thou this blade ought to be plunged into the body of the Consul!

Now truly, what is that damnable life of thine? For thus with thee I shall speak, so that not by hatred do I seem moved, hatred which is owed, but so that by mercy I am moved, mercy which for thee none is owed. Came'st thou a little while before into the Senate -- from so great a company as this and out of so many friends of thine and associates, who greeted thee? If this has happened within the span of human memory to no one, then a word of insult dost thou await, though by the most serious judgment of silence thou hast been crushed? What, given the fact that at thine entrance, those benches near thee empty were made, given that all the men of Consular rank who by thee thoroughly often to slaughter had once been marked, as soon as thou sat amongst them, that part of the benches bare and empty they abandoned; with what composure dost thou think thou must bear this?

By Hercules! If my slaves feared me in the same way as all thy fellow-citizens fear thee, I ought to leave mine home, I would think. Dost thou not think the same concerning thyself and the city? And, if I was by mine own fellow-citizens undeservedly suspected, so grave and offensive did I seem to them, then I would prefer to rather be absent from the sight of the citizens than to be scrutinized by the deadly-looking eyes of everyone. Since thou art aware that, because the guilt of thy wickedness, the hatred of all for thee is proper and for a long time owed, why dost thou hesitate? Art thou avoiding the sight and presence of those whose sensibilities and feelings thou art harming? If thy parents feared and hated thee so, and not were I able to please them them by any means, I am of the mind that thou shouldst withdraw from their eyes whithersoever. Now thee thy country, which is the common parent of us all, hates and also fears, and for a long time now has deemed that thou thinks of nothing but her parricide. Will thou neither revere her authority, nor follow her judgment, nor fear her power?

She, thy country, with thee, Catiline, thusly acts and in such a way, though silent, speaks:

“Up till now for so many years, no crime has existed apart from thee, no shamefulness without thee; murders of many citizens have been unpunished and freely done by thee, as well as the oppression and plundering of our allies. Thou hast been allowed to not only ignore laws and criminal investigations, but truly to turn them upside-down and thoroughly shatter them. Those past crimes, although they ought never to be endured, nevertheless as I have been able, I have endured them; now truly all of me is in fear on account of thee alone. No matter what sound is made in the night, Catiline is the object of our fear; no plot seems to be enact against me that does not come from thy wickedness -- these things are not to be endured. On account of this, leave and take also this fear from me! If my fear is true, then I shall not be destroyed by it; but if it is a false fear, then at last, finally, I shall cease from fearing.”If with thee, thusly as I have spoken, should thy country speak, ought she not to get her way, even if she is unable to apply force? What of the fact that thou didst give thyself into custody? That thou in order to avoid suspicion, said thou wished to dwell at Marcus Lepidus' home? By him thou were not received and even to me thou dared to come and asked if at my home I could keep thee. When by me also that response thou hadst received, that I, who am in great danger being already penned in the same city as thee, am in no way able to be safe within the same walls of my home with thee, thou came'st to Quintus Metellus, a Praetor. By him thou were sent away and to thine associate, a “most excellent” man, Marcus Metellus, thither thou made thy way. Of course, this man in guarding thee would be most careful, and of course in suspecting thee he would be most wise, and of course in punishing he thee would be most resolute; forsooth thou thought that! But how far from prison and chains does a man appear that he ought be if he himself has judged himself worthy of surveillance?

Since these things are so, Catiline, if thou art unable to die off with a calm state of mind, dost thou hesitate to go away into some other lands, to consign thy life, wrested from many just and owed punishments, to flight and loneliness? “Bring this motion,” saiest thou, “to the Senate for a vote”; for this is something thou art demanding and, if it pleaseth this body to decree that thou shouldst go into exile, thou art saying thou will carry out this thing. Nay, I shall not do this, for it is a thing at odds to my sensibilities -- but nevertheless I shall do something so that thou mayest understand how these men feel about thee. Leave from the city, Catiline! Free the Republic from fear! Go off into exile, if this is the word thou art awaiting to hear! What is it, Catiline? Is there anything thou dost perceive? Art thou turning thine attention to these men’s silence at all? They endure; they are quiet. Why dost thou await the authority of men to speak on thy behalf when the will of men who are silent thou canst very plainly see?

But if I were to say such a thing to this very fine young man, Publius Sestius, or if to a most brave man like Marcus Marcellus, then upon me, though I am Consul, in this very temple, in accordance with the law, the Senate would have set violence and hands. Yet, in regards to thee, Catiline, when they are quiet, they approve; when they endure, they decide; when they are silent, they shout. And not these men only, whose authority forsooth is dear to thee -- though to thee their lives seem most cheap -- but even those, the Roman Knights, the most esteemable and best men, and the rest of the most brave citizens who stand about the Senate, a crowd of whom thou wert able to see, and whose passion thou discern'st, and whose voices a little while before thou heard'st without. The hands and weapons of these people do I scarcely hold back from thee, and I have so for a long time now; but yet, these same men shall I easily influence, so that when thou leave'st this city, this city which for so long thou hast been dedicated to destroy, right up to the gates may the people follow thee to see thee off .

And yet, what am I saying? Would something change thee? Wouldst thou ever emend thyself? Wouldst thou think on any flight? Wouldst thou think upon banishment? Would that the deathless gods bestow that thought upon thee! And yet I see that if by my speech thou, having become exceedingly terrified, do set thy mind to go into banishment, such a great storm of ill feelings will be upon me! -- less so in this current time because of the fresh memory of thy wickedness, but surely more so in the hereafter shall this storm hang o'er me. But it is worth it, as long as the damn thing may stay a personal ruin and be dis-joined from the dangers to the Republic.

But thou? To be concerned about thy vices? to cower before the laws' penalties? to yield to the current state of the Republic -- nay, we must not ask these things of thee. For not art thou the sort of man, Catiline, that either shame has ever called thee back from a shameful act, or fear from danger, or reason from madness.

Because of this, as often I have already said, set out; and also, if thou dost wish to incite ill-will towards me, a personal enemy --as thou hast said before-- of thine, then straightaway make thy way into banishment. Scarcely shall I endure the gossip of the people, if this thing thou shalt do; scarcely the weight of such ill feelings shall I shoulder, if into banishment by the order of the Consul thou shalt have gone. But if thou prefer'st to be a slave to my praise and glory, go out with that ill-suited band of evildoers! Convey thyself to Manlius! Spur on thine abandoned fellow-citizens! Sever thyself from the good! Declare upon thy country war! Revel in ungodly rapscallionry so that by me not cast out to foreigners, but to thine own willing men to go thou seem'st.

But why should I call upon thee so often? I already know that men have already been sent -- yes, they who for thee at the Aurelian Forum are waiting in arms! I already know that decided and agreed upon with Manlius was the date for thy plans. I also already know about that silver eagle, a thing which for thee and thine I fully believe will be destructive and mournful, a thing for which an altar of thine wickedness was once set up at thy home -- but no longer, for I know that yon eagle has been sent ahead of thee! Since thou art not able to be absent from this thing any longer, this thing which thou used to worship when thou went out to slaughtering, from the altar of which thou hast often extended that unholy right hand of thine to the murdering of thy fellow-citizens.

Finally, thou shalt go at last, whither thy damnable lust, unbridled and ravenous, hath been thrusting thee; for not does this cause any pain to thee, but some certain unbelievable pleasure. For this madness Nature hath birthed thee, Desire hath molded thee, Chance hath preserved thee. Never hast thou lust after not only leisure, but not even a war unless it be dishonorable. Thou hast obtained a riotous band of the wicked from lost and ruined men, from men who, not only from all fortune, but even from all hope have been bereft. Here shalt thou some happiness enjoy, in some gladness thou shalt leap, in such pleasure shall thou be as a bacchante, when in such a number of thine neither shall thou hear of any good man-- none at all--nor shalt thou see one! To this life’s devotion have thy labors been borne, as when thou liest upon the ground not only to look out for any debauched desires, but even to commit actual crimes, and likewise when thou art awake in the dead of night to not only plot against the sleep of husbands, but even to steal away the goods of thy fellow-citizens. Thou hast a chance now where thou may'st show that famous tolerance of thine for hunger, for cold, for lacking everything - because of these things, thou shalt realize within in a short time that thou art already finished. I accomplished so much at that time when I rebuffed thee from the Consulship, so that as an exsul rather than a Consul thou wouldst try to oppress the Republic; and this revolution, which by thee hath been been wickedly undertaken, let it be named as an act of banditry rather than of war.

Now, so that I may ward off from my person by entreaty and prayer, Fathers and Enrolled, a certain nigh-justified complaint; listen, please, diligently, to what I shall say, and these things deep within your hearts and minds, there commit them. For if with me my country, which to me more than my life - much more!- is dear, yes, if the whole of Italy, if all the Republic could speak, she would say:

“Marcus Tullius, what art thou doing? Dost thou him, whom an enemy of the state thou hast found, whom a leader of war would be thou see'st, whom to be awaited for as the general in an encampment of the enemy thou realize, him who is a plotter of wickedness, a chief of conspiracy, a summoner of slaves and lost citizens -- to go dost thou allow'st him, so that from thee not sent from the city, but sent against the city does it not seem? Does this man not in chains be led, not to death be taken, not by the highest punishment to be butchered will thou command? What at last thee impedes? The precepts of the ancestors? But very often even private citizens in this Republic deadly fellow citizens by death they have paid. Are not the laws, which concerning punishments of the Roman People, consulted? But never in this city are there those who from the Republic have revolted, the laws of citizens have kept. Art thou the ill will of posterity afraid? Truly to the Roman People thou offer very fine thanks, the People who thee, a man by himself known by no esteem of his forefathers at so early an age to the highest office through all the steps of honor has lifted up; if because of the ill will or the fear of some danger the well-being of thine citizens thou disregard. But, if there is any fear of ill will, not more strongly must the ill will of severity and strength than of inaction and negligence be most feared? Or, when by war Italy will be laid waste, when attacked are the cities, the homes burnt, then thyself dost thou not think by a conflagration of ill will thou will be engulfed?"But I --to these most sacred of the Republic's words and to those men, who the same way feel, to their minds a few things shall I reply. If I this thing the best in doing were to judge, Father and Enrolled, that Catiline by death to be punished, then one hour's enjoyment to that damn gladiator to live I would not have given.

And for if the greatest men and the most illustrious by Saturninus' and the Gracchi's and Flaccus' blood -- and of many elder others -- not only themselves did not defile, but likewise did they themselves honor, then rightly to be afraid I did not have to be, lest any ill will because this parricidal murderer of the citizens has been slain might overflow over me into posterity. Even if this ill will were to so greatly hang overhead, nevertheless of this mind I have always been, that ill will by honor won is glory, not ill will - this what I believe.

Although several there are in this rank, who either these things, which are pressing, they do not see, or these things, which they do see, they ignore; these men who the hope of Catiline by mild opinions have nourished and the conspiracy, growing on account of disbelief, they have condoned; by whose authority many men, not only wicked, but inexperienced, if upon this man would have turned their attention, then cruelly and king-like to have been done they would say. Now I understand that if that bastard will have --whither he goes forth-- into the Manlian camps arrived, then there no one so foolish shall there be, who does not see that a conspiracy exists, no one so wicked who may not profess it. Moreover, when this one man has been slain, I understand that this plague of the Republic only for a short time is pushed back, not forever fully overwhelmed is it able to be. For if himself he shall have cast out and with himself his own friends he shall have led, and to the same place the rest of them from everywhere have been gathered, all those men like sailors after a shipwreck he will have summoned, then quenched and destroyed shall also be not only this so great a fully-grown plague for the Republic, but truly also the shoot and seed of all of the evils. And for long since, enrolled fathers in these dangers of a conspiracy and in plots we are found, but I know not how all this wickedness, and the long-standing rage and insolence -- they are ripe! -- at the time of my Consulship has burst out.

For if from such banditry that bastard, he alone, shall be carried off, we shall seem perhaps for a certain brief time from anxiety and fear to be relieved, yet a danger will set in and there it shall be, enclosed deep in the veins and in the bowels of the Republic. So often men who are ill with a serious disease and because of heat and fever are laid up, if icy water they drink, at first they relieved seem; but then much more seriously and violently are they struck, for thus this illness -- this illness which is in the Republic! -- which though relieved by the execution of that bastard, more violently in the remaining living conspirators shall grow serious.

On this account, let them withdraw, these wicked men!

Let them sever themselves from the company of the good!

Into one place let them flock together, from the wall at last, as often I already have said, let them be severed from us! Let them cease from plotting at their homes against the Consul, from standing around the assembly of the Praetor Urbanus, from besieging with swords the Senate-House, small hammers and torches for the burning of the city, from preparing these things -- cease! Let it finally be written on the brow of each one, how concerning the Republic each man feels! I promise this to ye, Father and Enrolled, that for us, the Consuls, there will be such diligence; for ye such authority; for the Roman Knights, such courage; for all good people, such harmony, that because of Catiline’s departure everything may be laid bare, lighted upon, overcome, and punished -- ye shall see.

To these very omens, Catiline, with the highest well-being of the Republic, with thy pestilence and destruction and with utter ruin of those who thee with thee in every wickedness and parricide have joined, set out to unlawful war and ungodliness! Thou, Jove the Father, who by these same omens this city by Romulus thou established; thou, whom as Stayer of this city and of the government truly we name, this man and his allies from thine and the rest of the gods’ temples, from the homes of the city and from the city walls, from the life and fortunes of the citizens thou shall keep them at a distance and the men who are enemies of the good, enemies of the state, bandits of Italy, who in a treaty of wickedness amongst themselves and in an ungodly alliance are joined, with everlasting punishments the living and the dead thou shalt pursue.

In Catilinam Orationes - The Catilinarian Orations

1 The Latin here is audacia, usually rendered as "boldness". I do not feel that the English word "boldness" encapsulates what Cicero is attempting to convey in this instance, so I have chosen "recklessness" or "insolence" as closer to the violent passions from which Catiline was said to have suffered.↩

2 Oft-cited textbook use of anaphora - the repetition of a word for effect, creating both emphasis and exasperation. The Latin Nihil is repeated here six times: "Nihilne...nihil...nihil...nihil...nihil...nihil - "Has not...has not...has not...has not...has not...has not...?" Nihil, lit. "nothing" is used here as a stronger negation than the usual non "not" and adds further emphasis to Cicero's exhaustion at Catiline's reckless and murderous behavior: "How could you possibly not be upset by the nightly guard on the Palatine - it's your fault the guard has to be there!"↩

3 Mons Palatinus, Palatium - The Palatine (Hill) - one of the seven hills of Rome, the Palatine (according to legend verified by archaeology), was the site of the first community of huts in Rome. It was also the site of the cave of the she-wolf which suckled Romulus and Remus. Standing at 40 meters above the Forum Romanum (which lies at its base between it and the Capitoline), this rocky outcropping served as an protective citadel, offering another defensive stronghold for the community (the akropoleis of the Greek city-states were employed for the same reason). During the Republican era, wealthy patricians kept their homes on the Palatine (Cicero purchased his home for an impressive 3.5 million sestertii); during the Principate, the Emperor and his court resided on this hill; as the Empire grew, so did the machinery of the Imperial Court which eventually swallowed this entire summit and whose ruins dominate the whole area to this day. Words denoting a "palace" or "palatial" are derived from this metonymy.

For a nightly guard to be set on the Palatine would be equivalent to setting a guarded force around the homes of the Senators in Washington, DC (and including the White House), measures which would be highly indicative of the seriousness of the situation.↩

.jpg) 4 The Temple of Jupiter Stator. The location of the temple is somewhat unclear, but it likely lay at the base of the Palatine at the end of the Forum opposite the Capitoline and Curia. The site was dedicated by Romulus to Jupiter (Jove the Father) who vowed the construction of the temple if the god would turn back the advance of the enemy Sabines which was causing the Romans to retreat up the Palatine; needless to say, the Sabines were defeated and Romulus had the ground dedicated and the temple constructed thereupon. It was well fortified and was synonymous with Roman defense, hence why Cicero decided to hold the Senate's meeting there - it would illustrate to the Senate and to the People who would have seen the Senators gathering there that there was some alarm about the city. It would be equivalent to watching the President of the United States broadcast a message warning of sedition to the People from the PEOC (Presidential Emergency Operation Center), where chief persons of the state are secure from outside attack. Cicero is alarmed that the enemy is not only within the walls of Rome, but within the walls of the Roman Senate's "defense bunker".↩

4 The Temple of Jupiter Stator. The location of the temple is somewhat unclear, but it likely lay at the base of the Palatine at the end of the Forum opposite the Capitoline and Curia. The site was dedicated by Romulus to Jupiter (Jove the Father) who vowed the construction of the temple if the god would turn back the advance of the enemy Sabines which was causing the Romans to retreat up the Palatine; needless to say, the Sabines were defeated and Romulus had the ground dedicated and the temple constructed thereupon. It was well fortified and was synonymous with Roman defense, hence why Cicero decided to hold the Senate's meeting there - it would illustrate to the Senate and to the People who would have seen the Senators gathering there that there was some alarm about the city. It would be equivalent to watching the President of the United States broadcast a message warning of sedition to the People from the PEOC (Presidential Emergency Operation Center), where chief persons of the state are secure from outside attack. Cicero is alarmed that the enemy is not only within the walls of Rome, but within the walls of the Roman Senate's "defense bunker".↩ 5 November 6th and 7th respectively. Catiline met with his cohorts at Marcus Laeca's home on the night of November 6th. It was the following morning of the 7th in which the two knights were barred from entering Cicero's home, for the Consul had learned of their murderous intentions. This is most likely the first time that Catiline had learned that Cicero was watching him - hearing the Consul refer to a secret nighttime meeting held by him when all good Romans should be home in bed must have been alarming. ↩

6 I’ve chosen to leave this untranslated, as the phrase has survived all the way to modern usage in its original form in multilingual publications (English-speaking political editorials are abound with this immortal phrase). More importantly, “O such times! O such morals!” just doesn’t seem to have the same damning ring to it as the Latin.↩

7 Consul- “Advisor” - the two Consuls were the supreme executive magistrates of the Roman Republic. Essentially, the office of Rex (King) was broken between two persons elected by majority. They held almost equal power (the first to garner the most votes was named First Consul and so procedurally voted before his colleague). These magistratus maiores (“Greater Magistrates“) were the presidents of the Senate and guided the Senatorial agenda. They had absolute veto power, even over each other. Each were protected by twelve lictores (bodyguards) upon their person as they walked through the city, and they had the right to wear the toga praetexta, (“purple-bordered toga” - a white toga decorated with a broad red/purple stripe three inches wide along the edge) and the right to sit the sella curulis (the Chariot’s Chair - a chair symbolic of power and authority as it has no back and low arms, symbolizing the weariness and uncomfort of a long sit and not doing one’s task in a timely and efficient manner: one‘s authority is not everlasting). The Roman year was named after the two Consuls (i.e. “in the Consulship of Caesar and Bibulus” = 59 B.C.) much like the Eponymous Arkhons of Classical Athens.↩

8 Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio -183 - 132 B.C. - a member of the House of Cornelius and of the Scipio branch (meaning "rod, staff", the progenitor of the clan acted as a guide for his blind father, serving [poetically] as his father's walking stick). He was the first Scipio to be called Nasica -"sharp nose", and further "Serapio", a nickname given to him by his chief rival, the People's Tribune, Gaius Curatius. The latter name was in reference to some slave (referred to as "a vile slave of a pig-jobber" by Pliny the Elder) who belonged to a dealer in sacrificial animals named Serapio and with whom Nasica bore a striking resemblance. Nasica instead embraced the name, thus nullifying the insult.

He was cousin to Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, adoptive grandson of the famous Africanus who defeated Hannibal; this Scipio Aemilianus was the destroyer of Carthage at the end of the 3rd Punic War (149 - 146 B.C.), which put his side of the family at odds with Nasica's father, who implored the Senate to save Carthage. The two branches would unify in their opposition to the reformist People's Tribune, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus.

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus was also a cousin of these two Scipiones, but he was a demagogue who threatened Senatorial order through progressive reforms involving agrarian redistribution (the Lex Sempronia Agraria of 133 B.C.), shortening the length of military service, expanding citizenship to the Italian socii (allies and confederates), and allowing socio-economic classes other than Senators to act as Judges. Gracchus had circumvented the influence of the Senate by taking his legislation immediately to the Concilium Plebis (The People's Assembly); though not an illegal act, it did snub men who were not accustomed to being snubbed. When the Senate convinced another Tribune, Marcus Octavius, to use his Tribunician veto power to stop the proceedings, a duel of vetoes seemed inevitable; so Tiberius Gracchus had Octavius forcibly removed from the proceedings, thus violating the sacrosancitity of a tribune, an act of extreme blasphemy. Through winning re-election, Gracchus stymied the efforts of the Senators who sought to prosecute him at the expiration of his term (prosecution of a sitting magistrate being forbidden); the Senators resorted to bloodier means to get their way. When Tiberius Gracchus was making his way to the Capitoline, the People had gathered in a great unruly mob. Gracchus told his supporters who set about him as a body that if he felt in danger, he would point to his head as the signal for aid. Fighting broke out as he was walking by the Curia and he gave the agreed-upon signal. The Senators' agents, seeing that the progressive reformist demagogue was beset on all sides by armed men and was pointing to his head, took this to mean that he was calling for himself to be crowned as a king over them. When the Senators gathered inside the Curia were told of this, they shouted in horror and anger (kingship being a form of government most vile to Roman feelings - they akinned it to slavery); when Nasica shouted for the Consul to act and deliver them from slavery, the Consul refused on the grounds that no citizen should be put to death without trial. Nasica cried:

"Since, then, the chief magistrate betrays the state, do ye who wish to succour the laws follow me."

With these words he covered his head with the skirt of his toga and set out for the Capitol. All the senators who followed him wrapped their togas about their left arms and pushed aside those who stood in their path, no man opposing them, in view of their dignity, but all taking to flight and trampling upon one another.

-Plutarch, Life of Tiberius Gracchus XIX

The Senators, bearing the remains of broken furniture as clubs, marched their way up to Gracchus and beat him and three hundred of his supporters to death. Their bodies were thrown into the Tiber as one last infamy. In true Mediterranean fashion, Gracchus was avenged: both Scipiones, Aemilianus and Nasica, were killed, both within a few years, by compatriots of Tiberius Gracchus.

Cicero is asking that if Nasica (as a private citizen!) could have put Tiberius Gracchus to death with no trial for even slightly undermining the Republic, then why should he (the Consul, who holds more power than a private citizen) allow Catiline to still live?↩

9 Pontifex Maximus - "Greatest Bridgebuilder (?)" (often rendered into English as "High Pontiff") - the high priest of the Roman state religion. The word pontifex is of dubious etymology, but is most likely a combination of pons, pontis m. "bridge" and the agentival suffix -fex ("maker, doer, builder") derived from facio, facere, feci, factus "to make, do". The original pontifices perhaps were responsible for constructing or consecrating bridges (seen as a sacred act), or they bridged the gap between the mortal world and the divine (Van Haeperen holds this reading). Either literal or metaphysical explanation (or both) is adequate.

The office of Pontifex Maximus dates back to Rome's second king, Numa Pompilius, who perhaps reigned from 715 to 673 B.C. This Sabine was a peaceful ruler and was most greatly focused on Rome's religious practices, appointing priesthoods for the Romans and establishing their disciplinae "teachings". After the abolishment of the Monarchy, the office of Rex ("King") was stripped of its military and political power and renamed Rex Sacrorum, "the King of Sacrifices", who carried out the religious duties once done by the Rex; but unlike the Rex Sacrorum, the Pontifex Maximus could (and was expected to) hold both military and political office. Once forbidden from leaving Italy, it was Scipio Nasica Serapio (cf#7) who was the first to break the taboo which quickly lost the reverence the office once had; for Gaius Julius Caesar was elected Pontifex Maximus in 63 B.C. and retained the post until he died in 44 B.C. - within those years he had held the offices of Consul, Proconsul, and Dictator and traveled the world over from Spain to Germany to Egypt to Syria.

The Pontifex Maximus resided in a state-kept home near the Regia ("The Kingshome") and the Aedes Vestae ("The Temple of Vesta) in the Roman Forum, and his duties included: overseer of the state calendar, consultation on omens and portents (lightning, plague, strange auguries), conducting all legal patrician marriages, consecrating new temples and sacred buildings, acting as chief justice of the adoption and succession office, and regulation of public morals and fining of religious heresy.

|

| http://condor.depaul.edu/sbucking/296A05_over14.htm |

|

| http://condor.depaul.edu/sbucking/296A05_over14.htm |

The office passed into the Catholic Church - the Pope is still referred to (unofficially) as the High Pontiff and Pontifex Maximus.↩

10 Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus - Cf.#8↩

11 "For other precedents -- which are exceedingly ancient --- I pass over."- preterition (Lat: praeteritio - "a passing over") is when one says that they have no intention of mentioning a thing, but by the fact that he had just mentioned it, had brought the thing to the listener's mind. Cicero claims that there are other precedents to executing Catiline, but he does not wish to mention them; instead he proceeds to mention them in rather exacting detail. This rhetorical device will be utilized elsewhere in the speech.↩

12 Gaius Servilius Ahala - A member of the House of Servilius, this Ahala was the Magister Equitum (Master of the Horse, the second of the Dictator, who was forbidden to sit a horse and so acted in his stead) of the Dictator Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who was holding the office for the second time. When the Plebeian Knight Spurius Maelius sought to win himself a kingship over the Republic in 439 B.C., Cincinnatus, newly appointed as Dictator, summoned Maelius to answer to him; Maelius refused and instead attempted to rouse the People to his defense. Ahala tracked him down and, with a dagger concealed in his armpit (Ahala/Axilla "armpit" was an aetiological legend used to explain the origin of the name) slew the revolutionary.↩

13 Spurius Maelius - an extremely wealthy Plebeian Knight who bought up enormous quantities of corn from the fertile fields of Etruria and sought to use the influence of controlling the food supply to win himself a kingship. The Senate elected Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus to the Dictatorship for a second time to combat the growing feelings of revolution. Gaius Servilius Ahala was named the Dictator's second, the Magister Equitum (Master of the Horse), who tracked Maelius down and slew him with a dagger hidden in his armpit when the revolutionary refused to answer the summons of the Dictator.(cf.#12)↩

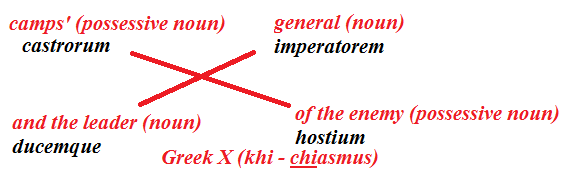

14 "a deadly citizen rather than a most bitter enemy" - The Latin here is pretty cool: civem perniciosum quam acerbissimum hostem". This is the textbook example of chiasmus, a stylistic device which, when arranged so that the nouns align and the adjectives align, creates an X, the Greek letter khi (chiasmus):

Cicero creates a very strong contrast between the two, showing that it doesn't take much for the deadly citizen to cross over (literally) into the realm of an enemy of the state; ergo, a troublesome citizen must be stopped before he can rise up against the Republic.

As far as I am aware, this sort of configuration is so clunky and awkward in English that no native examples are extant.↩

15 Senatus Consultus - “The Senate’s Resolution/Decision/Decree” - an executive order passed by a motion of the Senate with the force of martial law. After the death of the former Dictator Sulla (80 B.C.), the Senate was wary to elect another Dictator - what if the next Dictator decided to emulate Sulla and shatter the Constitution by remaining in his autocratic office perpetually (which is exactly was Caesar did from 49 - 44 B.C.) as Sulla could have done if he had so wished? The Senate attempted to usurp Dictatorial powers by passing a Senatorial Decree, which suspended ordinary law and invested the Consuls with absolute power over the lives of conspirators and other unsavory types plotting against the Republic. Cicero was right to describe the Senatorial Decree as “vehemens et grave” (“powerful and serious”) - Catiline’s life was technically in Cicero’s hands. This particular Decree was passed on October 21st (Cicero claims that twenty days have passed since the Decree's passage and this speech's reading).↩

16 Lucius Opimius was the Roman Consul for 121 B.C. He is most famous for executing approximately 3,000 Roman citizens without trial, citing the extraordinary powers granted to him by the Senatorial Decree as legalization for the act. The slain citizens were supporters of the populist reformer, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, younger brother of the People's Tribune, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (cf. #7). Gaius Gracchus had won great accolades and respect from the People, even more so than his elder brother for the popular legislation he was proposing. The Senate tried a new tactic in dealing with this progressive reformist: they stole his agenda. The Senate worked through another Tribune, Livius Drusus to not only propose Gracchus-esque reforms in the Senate's name, but make these reforms even more progressive and populist: for example, when Gracchus wished to send out a two colonies and populate them with citizens, the Senate balked at the request, accusing him of attempting to curry popular favor; however, when Livius Drusus proposed twelve colonies, the Senate approved. When Gracchus attempted to offer redistributed land at a low-rent price, the Senate again accused him of attempting to win the support of the People; then they had Livius Drusus draft the same legislation, only rent-free. In such a way, the People began to grow more warmly towards the Senate. When Lucius Opimius was elected Consul for 121 B.C., he was joined by Livius Drusus and others to unseat Gracchus from his Tribuneship - they planned to force Gracchus and his supporters to incite violence, thus giving them the pretext to pass a Senatorial Decree and rid themselves of another Gracchus; Gracchus, however, refused to turn to violence, despite the feelings of many of his supporters, such as Marcus Fulvius Flaccus who thought violence was a fine alternative. Due to the machinations of Opimius, one of his own supporters was killed by the supporters of Gracchus, and in this way he was finally given the chance to propose and pass the Senatorial Decree, giving himself (for the first time in Roman history, says Plutarch) Dictatorial powers. Even though Gracchus still preached non-violence, his supporters under Fulvius had been whipped into a frenzy and, fully armed, a great many of them made their way to the Aventine Hill to prepare themselves in for a brawl with the Senators and their agents. Gracchus tearfully bid farewell to his wife, Licinia (sister of Marcus Licinius Crassus the triumvir) and sadly followed his rowdy supporters, armed only with a short dagger in the folds of his toga.

Gracchus and Fulvius, from a defensive position on the Aventine sent Fulvius' youngest son as a herald bearing a staff of war to the Senate to offer terms of negotiations. Opimius balked at being spoken to by a child and bid the boy return to his father and have the man and Gracchus come themselves to him. The father, upset by such an answer, sent the boy back with further terms. Opimius ordered the boy's arrest and led his contingent of Cretan archers (the ancient world's snipers, who just conveniently happened to be on hand...) to the Aventine.

In the ensuing violence, Gracchus was slain, along with Marcus Fulvius and his elder son who attempted to hide from the Senate's attack; Fulvius' other son, the arrested herald, was also executed later on Opimius' commands - it is noted that the Consul allowed the child to choose the manner of his death.

Gracchus' head was chopped off and carried to Opimius, who had offered its weight in gold to the bearer - said bearer, a certain Semproneianus, raised some eyebrows when Opimius weighed the head and discovered it to weigh around seventeen pounds. Opimius, not appreciating the attempted deception authored by this enterprising murderer who had scooped out the brains beforehand and filled the skull with lead, sent him off with nothing.

Gracchus' head was chopped off and carried to Opimius, who had offered its weight in gold to the bearer - said bearer, a certain Semproneianus, raised some eyebrows when Opimius weighed the head and discovered it to weigh around seventeen pounds. Opimius, not appreciating the attempted deception authored by this enterprising murderer who had scooped out the brains beforehand and filled the skull with lead, sent him off with nothing. Nearly three thousand of Gracchus' supporters, Roman citizens, were executed without trial.

The Temple of Concord was built by Opimius to honor this victory - the People found it in extremely bad taste that a temple dedicated to harmony would mark the slaying of citizens.

Such ended the life of a second Gracchus at the Senate's hands. In the context of the speech, let us keep in mind that Cicero would have the Senate believe that Catiline's crimes and conspiracy outstrip those of the aforementioned who, being Roman citizens --and children!--executed without trial, were slain nearly on sight by strong heroes of the Republic. If that is his argument, then the orator must explain why he, the quasi-Dictator, has not acted to save the Republic from such a dangerous criminal, even worse than those Gracchus brothers and Fulvius and his children.↩

17 "the Consul should see to it lest the Republic any harm suffer" - "ne quid res publica detrimenti caperet" - this is a minor re-wording of the basic formula for such a Senatorial Decree (cf.#15) The Consuls were told to take whatever action necessary to save the Republic: videant consules nequid res publica detrimenti capiat. - "Let the Consuls see to it lest the Republic any harm suffer". This is the justification for the murdering of Roman citizens without putting them first on trial.↩

18 Gaius Sempronius Gracchus - younger brother of Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (cf. #9). Like his brother, this Populist reformer met a messy end at the hands of the Senate and the Consul, Lucius Opimius (cf.#16).↩

19 Cf.#8 for the illustrious line of the Sempronii Gracchi and their relations the Cornelii Scipiones.↩

20 Marcus Fulvius Flaccus - Populist reformer who was slain with his sons and Gaius Sempronius Gracchus (cf.#16).↩

|

| Gaius Marius |

He allied himself with Lucius Saturninus, a third reformist Tribune of that span of decades in the late 2nd century/early 1st century B.C. dominated by the murders of the brothers Gracchus for their reformist careers in politics. They were joined in their ambitions by Gaius Servilius Glaucia, who was elected Praetor for the same year. The three formed the Alpha (or Proto-) Triumvirate (the 1st Triumvirate being an unholy alliance between Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus in the 60s/50s B.C.; the 2nd Triumvirate of Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus of the 30s B.C.) and together pushed through a shockingly progressive agrarian allotment bill which divvied up the plots of fertile land in Gallia Cisalpina ("Nearer Alpine Gaul" - the region of the peninsula north of the Padua [Modern day Po] River and south of the Alps), which had just been conquered by Marius and was to be awarded to Marius' veterans for their service (how convenient!) During the voting, the Triumvirate's opponents attempted to break up the meeting to halt the proceedings. During the scuffle, some Senators claimed they had heard lightning, an ill omen signaling the close of business; the voting was to be declared null and void. Saturninus told the Senators to sit down and remain silent, lest hail would follow the thunder; the voting continued and thus the Leges Appuleiae were passed.

Marius, horrified at the possibility of being overshadowed by his colleagues, broke with the two of them; on their own without the great Marius, these two saw their only hope of avoiding prosecution by an enraged Senate was to continue to hold office (prosecution of a sitting magistrate being illegal) by any and all means. When the voting for 99 B.C. was occurring, Saturninus managed to secure his third Tribuneship, but Glaucia, who was already running an illegal candidacy for not observing the two year moratorium on holding office between Praetor and Consul (a most abused regulation; Marius was Consul seven times in all, despite the legal ten year wait between holding the office.) appeared to be in trouble: Marcus Antonius Orator (grandfather of the famous Triumvir) was certain to be elected, but another candidate from the Senatorial Party, Gaius Memmius, seemed to be poised to take the co-Consul's chair. Operating under the given that a person running for office should be alive, Glaucia and his supporters beat this poor man to death in Field of Mars while the voting was happening. The Senate, fearing further violence and revolution, and most likely still smarting from Saturninus' earlier insult, passed the Senatorial Decree, forcing Marius to arrest his once-colleagues (one imagines with relish). The newly-made enemies of the state, after losing a pitched battle on December 10th with the forces of the Senate in the Forum Romanum, withdrew to the citadel on the Capitoline, where they soon found themselves in even direr straits when a no-nonsense Marius shut off their water supply. The abject creatures surrendered and left the protection of the citadel under the oath that they would be escorted to the Curia; instead (echoing the fate of the would-be tyrant Kylon in Athens in 626 B.C.) these men were slain by members of the Senatorial party who mounted the nearby rooftops and threw the rooftiles (heavy, sharp-angled things) at hand upon their heads, splattering their brains upon the Forum pavement.

And thus more revolutionaries -- more precedents -- were slain.

Cicero would like the chamber to note that not even a single night passed between the Senate granting the Dictatorial powers to Marius and his co-Consul and the slaying of the revolutionaries; why has Catiline been allowed to survive for twenty days?↩

22 Lucius Saturninus - the third famous reformist Tribune of the late 2nd century/early 1st century B.C, who was slain by the Senatorial party after the Senatorial Decree was passed and power was given to the Consul Gaius Marius (once a colleague of both Saturninus and Gaius Servilius Glaucia) in order to suppress the revolution (cf.#21).↩

23 Gaius Servilius Glaucia - a member of the House of Servilius, this Glaucia allied with Gaius Marius and Saturninus. He was slain by the Senatorial party after the Senatorial Decree was passed and power was given to the Consul Gaius Marius (once a colleague of both Saturninus and Gaius Servilius Glaucia) in order to suppress the revolution (cf.#21).↩

24 Praetor - “He Who Is Foremost” - an elected position under Consul. There were originally two, but the expanding empire needed more: by the time of Caesar, the number had been raised to ten (Augstus would set the number at twelve, Tiberius to sixteen). Originally a military rank denoting a field marshal, the Republican Praetors were essentially chief justices with military generalships. Within the city or the field, they held sway, unless vetoed by a Consul. Propraetors were given command of provinces after serving their annual term as a Praetor. These magistratus maiores each had six lictores upon their person as they walked through the city, the right to wear the toga praetexta, and the right to sit the sella curulis. ↩

25 The Senatorial Decree was passed on October 21st.↩

26 castra, castrorum n. - "camps"- the word usually appears only in the plural and denotes a military encampment laid out in a rectangular polygon marked by a fossa ("ditch") an agger (the mound of earth raised by digging the fossa) and a vallum (cf. Eng. "wall" - the palisade set into the agger).

The military camps were only to be laid out by lawful armies of the Republic. Camps mustered and unsanctioned without the auspices of a magistrate wielding imperium ("commanding power") were highly illegal, alarming, and indicated that time for soft tones and careful treading had ended.↩

27 Etruria - a region of Italy northwest of Rome (dark brown on the map below) which was separated from that city by the Tiber River and the Silva Cominia (Cominian Forest). Etruria was the ancient home of the Etruscans, a dominant civilization of ancient Italy which peaked c. 650 B.C. and strongly influenced Roman rituals, dress, alphabet (modified from the original Greek colonists of the southern Italian Peninsula) and architecture. By 500 B.C., the Romans had expanded their own influence and territories to the point that the Etruscans were absorbed into the fledgling Empire.↩

28 Another noteworthy example of chiasmus (cf. #14). The stylistic device is not used to contrast the differences between the two nouns (as in #14), but this interlocking word order is meant to show a strong connection between the two: Catiline is both the general of these camps and the leader of the enemy.↩

29 Twelfth Day Before the Kalends of November = October 21st.↩

30 Sixth Day Before the Kalends of November = October 27th.↩

31 Fifth Day Before the Kalends of November = October 20th.↩

32 Praeneste - modern day Palestrina, Praeneste is located some twenty-two miles east of Rome along the ancient Via Praenestina. In its earliest times, Praeneste was an Etruscan (or heavily Etruscan influenced, given the number of Etruscan artifacts found there) city which came under the hegemony of the Latin League before the League's leading city of Alba Longa was destroyed by the Romans - afterwards, she was allied with Rome. Abandoning Rome during the latter's sack by the Gauls in 390 B.C., she was eventually conquered by Cincinnatus and brought under Rome's control.

After the defeat and death of Marius in 86 B.C., his son, Marius the Younger won the Consulship for 82 B.C., though underage and under-experienced - his rise was a political move by Sulla's opponents to prop up a popular leader around whom the elder Marius' veterans could rally. Upon doing so and openly declaring themselves as antagonists to Sulla, the Dictator was presumably displeased and carried out a campaign with his usual zeal. After losing a battle, Marius and his forces of seven thousand (who had absconded from Rome with the Capitoline treasury) found themselves blockaded within the walls of Praeneste, and after several failed escape attempts (including one which tunneling under the walls to safety), Marius the Younger committed suicide. The male population of Praeneste was slaughtered in the process, Sulla set up a military colony on the city's territory, and the inhabitants moved themselves from the higher ground of the Apennines to the lower, flatter plain at the range's feet.

Some twenty years later, Cicero still refers to Praeneste as "illam coloniam - yon colony".

33 Kalends of November = November 1st.↩

No comments:

Post a Comment